- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published:

Characteristics and impact of interventions to support healthcare providers’ compliance with guideline recommendations for breast cancer: a systematic literature review

Implementation Science volume 18, Article number: 17 (2023)

Abstract

Background

Breast cancer clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) offer evidence-based recommendations to improve quality of healthcare for patients. Suboptimal compliance with breast cancer guideline recommendations remains frequent, and has been associated with a decreased survival. The aim of this systematic review was to characterize and determine the impact of available interventions to support healthcare providers’ compliance with CPGs recommendations in breast cancer healthcare.

Methods

We searched for systematic reviews and primary studies in PubMed and Embase (from inception to May 2021). We included experimental and observational studies reporting on the use of interventions to support compliance with breast cancer CPGs. Eligibility assessment, data extraction and critical appraisal was conducted by one reviewer, and cross-checked by a second reviewer. Using the same approach, we synthesized the characteristics and the effects of the interventions by type of intervention (according to the EPOC taxonomy), and applied the GRADE framework to assess the certainty of evidence.

Results

We identified 35 primary studies reporting on 24 different interventions. Most frequently described interventions consisted in computerized decision support systems (12 studies); educational interventions (seven), audit and feedback (two), and multifaceted interventions (nine). There is low quality evidence that educational interventions targeted to healthcare professionals may improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. There is moderate quality evidence that reminder systems for healthcare professionals improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening. There is low quality evidence that multifaceted interventions may improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening. The effectiveness of the remaining types of interventions identified have not been evaluated with appropriate study designs for such purpose. There is very limited data on the costs of implementing these interventions.

Conclusions

Different types of interventions to support compliance with breast cancer CPGs recommendations are available, and most of them show positive effects. More robust trials are needed to strengthen the available evidence base concerning their efficacy. Gathering data on the costs of implementing the proposed interventions is needed to inform decisions about their widespread implementation.

Trial registration

CRD42018092884 (PROSPERO)

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women with 2.3 million new cases estimated in 2020, accounting for 11.7% of all cancers [1]. It is the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, with 685,000 deaths [1]. Breast cancer diagnosis is more frequent in developed countries [2]. Controlling and preventing breast cancer is an important priority for health policy makers [3].

Treatment procedures have rapidly evolved over recent years. As new and precise diagnosis strategies emerged, early treatment and prognosis of breast cancer patients have shown great progresses [4]. Advances in breast cancer screening and treatment have reduced the mortality of breast cancer across the age spectrum in the past decade [5,6,7]. Although the use of research evidence can improve professional practice and patient-important outcomes, considering also the huge volume of research evidence available, its translation into daily care routines is generally poor [8, 9]. It is estimated that it takes an average of 17 years for only 14% of new scientific discoveries to enter day-to-day clinical practice [10].

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) provide recommendations for delivering high quality healthcare [11, 12]. However, the impact of CPGs depends not only on their quality, but also on the way and the extent to which they are used by clinicians in routine clinical practice. Large overviews show that approximately 50% of patients receive from general medical practitioners treatments which differ from recommended best practice [13,14,15,16]. In the area of breast cancer, previous systematic reviews have shown that compliance with breast cancer CPGs [17], as well as for other types of cancer [18,19,20], remains suboptimal. A recent systematic review from our research group [21] found large variations in providers´ compliance with breast cancer CPGs, with adherence rates ranging from 0 to 84.3%. Sustainable use of CPGs is also notably poor: after 1 year of their implementation, adherence decreases in approximately half of the cases [22].

Suboptimal compliance with CPGs recommendations could increase healthcare costs if healthcare resources are overused (e.g., overtreatment, overuse of diagnosis or of screening techniques); but also, if they are underused (i.e., increased costs to cover the additional health care needs that people may face with worsening conditions due to under-used resources). Available evidence suggests that outcomes may improve for patients, healthcare professionals and healthcare organizations if decision-makers adhere to evidence-based CPGs [23, 24]. This is supported by a recent meta-analysis from our group [25], which suggests that compliance with CPGs is probably associated with an increase in both, disease-free survival (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.35 (95% CI from 0.15 to 0.82)) and overall survival (HR = 0.67 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.76). Developing interventions to support clinician uptake of breast cancer CPGs is therefore essential for improving healthcare quality and patient important outcomes. Although several interventions to support compliance with breast cancer CPGs have been proposed, no previous study has systematically examined their characteristics and effects.

The aim of this systematic review is to characterize and evaluate the impact of available interventions to support healthcare providers’ compliance with CPGs in breast cancer care.

Methods

Design

We conducted a systematic literature review adhering to the PRISMA reporting guidelines [26] (PRISMA 2020 Checklist available at Additional file 1). In this review, we addressed the following two questions: (1) What type of interventions have been used to support healthcare professionals´ compliance with breast cancer CPGs? and; (2) What type of interventions can effectively support healthcare professionals’ compliance with breast cancer CPGs? We registered the protocol in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO registration number CRD42018092884).

Searches

We searched for systematic reviews and original studies in MEDLINE (through PubMed) and Embase (through Ovid) using predefined search strategies from inception to May 2021 designed and implemented by an information specialist (IS) from the Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre (IS). The search strategies (available in Additional file 2) combined MeSH terms and keywords.

Study selection

We applied the following inclusion criteria:

-

Population: healthcare professionals providing health services related to the prevention or management of breast cancer. All types of healthcare professionals, and from any setting were included.

-

Intervention: interventions explicitly aimed at supporting or promoting healthcare professionals’ compliance with available breast cancer CPGs. Such guidelines may address any specific aspect of breast cancer care, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, surveillance or rehabilitation.

-

Comparator: any comparator, including also studies not using a comparator group.

-

Outcome: quality of breast cancer care (based on healthcare professionals’ compliance rate with breast cancer CPGs recommendations, but also on their knowledge, attitudes or self-efficacy concerning such recommendations); intervention implementation (fidelity, reach, implementation costs), and; patient health-related outcomes (e.g., survival).

We included experimental (randomized controlled and non-randomized controlled trials), observational (before-after, cohort, case-control, cross-sectional, and case studies), and qualitative or mixed-methods studies. Due to constrained resources, we only included studies published in English. One author (of IRC, DC, APVM) screened the search results based on title and abstract. A second author (ENG, LN, ZSP, EP, DC, APVM, GPM) independently reviewed 20% of all references. Two authors independently assessed eligibility based on the full text of the relevant articles. Disagreements were discussed (involving a third author when needed) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

One author (ENG, IRC LN, ZSP, EP, DC, APVM, GPM) extracted the following data about the characteristics and results of the included studies using an ad hoc data extraction form which had been piloted in advance: publication year, study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial), study location, setting, number of participants, aim of the study, type of breast cancer guideline (e.g., breast cancer screening), type of intervention (e.g., computerized decision support systems), and outcome(s) assessed (e.g., compliance rate). A second author (ENG, IRC LN, ZSP, EP, DC, APVM, GPM) cross-checked the extracted data for accuracy.

Quality assessment

We used the following tools to determine the risk of bias of the included studies: the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB I) [27], the ROBINS I tool for non-randomized controlled before-after studies [28], the Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group [29], the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies [30], the AXIS tool for cross-sectional studies [31], and the MMAT tool [32] for mixed methods studies. The specific criteria included by each of these tools are available in Additional file 3. One author determined the risk of bias of the included studies, and a second author cross-checked the results for accuracy. Disagreements were solved with support from a senior systematic reviewer.

Data synthesis

We described the characteristics and the effects of the interventions narratively and as tabulated summaries. Findings are synthesized by type of intervention. We applied the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization Care Review Group (EPOC) [33] taxonomy to classify our findings according to the types of interventions identified. Whereas for the characterization of the interventions we included all the publications identified meeting our eligibility criteria (irrespectively of their design); for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions we focused only on those studies following a suitable design for such purpose [34]: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled before-after studies, non-randomized controlled trials, and interrupted time series. Although we planned to conduct a meta-analysis on the impact of the interventions on compliance rates, this was finally not feasible due to the inconsistent and poor reporting. Instead, we provide a graphical quantitative description of the compliance rates before and after the implementation of the interventions.

Certainty of the evidence

Following the GRADE approach [35], we rated the certainty of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low, taking into consideration risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias. This was done by one researcher. and cross-checked by a second reviewer.

Results

Search results

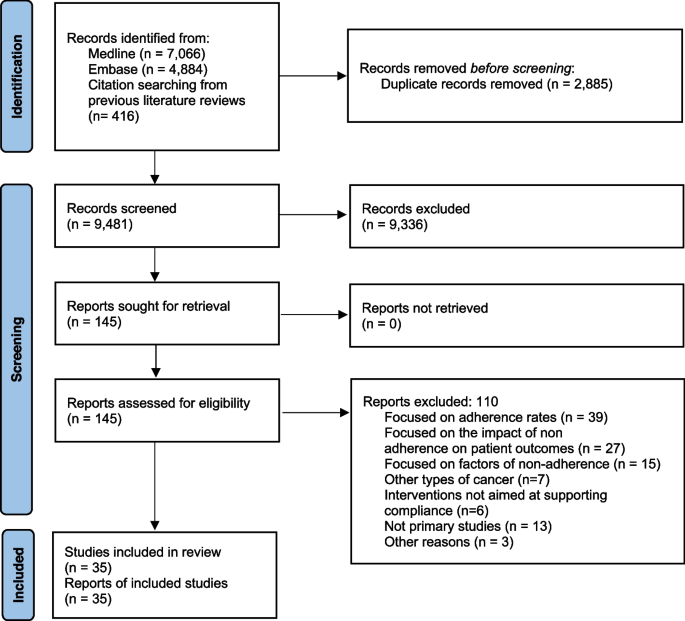

The eligibility process is summarized in a PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1). We retrieved a total of 9065 unique citations from database searches, which were reviewed (through screening by title and abstract) along with 416 additional references identified from the thirteen systematic reviews also identified. We selected 145 references for full text revision, from which 35 primary studies (reporting on 24 different interventions) were finally included in our systematic review [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70].

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 and described in detail in Additional file 4. Most (86%) were published from 2000 onwards. The studies were conducted in six countries: 15 (42%) were conducted in USA [37, 44,45,46, 49,50,51, 53,54,55,56,57,58, 60, 70], 12 (34%) in France [38,39,40,41,42,43, 63,64,65,66,67,68], 3 (9%) in the Netherlands [52, 62, 69], and 3 (9%) in Canada [36, 59, 61]. The remaining two studies were conducted in Australia [47], and Italy [48]. Eleven studies described interventions to support compliance with guidelines on diagnosis and treatment [41, 43, 52, 56, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70], 9 focused on treatment only [38,39,40, 42, 47,48,49, 62, 63], 5 on diagnosis only [45, 51, 58,59,60], and 7 on screening [36, 37, 46, 50, 54, 57, 61]. Six studies were randomized controlled trials [37, 45, 50, 51, 54, 60], four were non-randomized controlled trials [46, 57, 58, 63], eight non-controlled before-after studies [42, 49, 53, 55, 59, 62, 65, 69], one prospective cohort study , three cross-sectional studies [44, 47, 56], one mixed-methods [36] and twelve case studies [38,39,40,41, 43, 48, 52, 61, 64, 66,67,68].

Thirty of the 35 studies (85%) evaluated the impact of the interventions on compliance rate [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 53,54,55,56, 58,59,60, 62, 63, 65,66,67,68,69,70]. Four studies [43, 46, 50, 57] evaluated the impact on determinants of behavior change related outcomes (providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy about the CPGs recommendations). Two studies evaluated intervention adoption and fidelity [36, 44]. No study evaluated the impact of the intervention on patient outcomes, and only one study [44] evaluated the costs of implementing the interventions.

Characteristics of the interventions to support compliance with breast cancer clinical practice guidelines

Table 2 describes the characteristics of each type of intervention. Twelve studies described two different interventions consisting in the implementation of computerized decision support systems [38,39,40,41,42,43, 48, 64,65,66,67,68], 7 described 6 different educational interventions targeting health care professionals [44, 50, 55, 57,58,59, 63], 9 described 9 multifaceted interventions [36, 37, 46, 49, 51, 53, 54, 60, 62], and two studies described two audit and feedback interventions [47, 69]. The rest of the studies described interventions based on: implementation of clinical pathways [56], integrated knowledge translation systems [61], medical critiquing system [52], medical home program [70], and reminders to providers [45].

Computerized decision support systems

The use of computerized decision support systems to promote compliance with breast cancer CPGs was described in 12 studies [38,39,40,41,42,43, 48, 64,65,66,67,68]. Eleven of them reported the same intervention, which consisted of a system developed in France called OncoDoc [38, 40–43, 64–68). OncoDoc is a computerized clinical decision support system that provides patient-specific recommendations for breast cancer patients according to CancerEst (local) CPGs [71]. A study conducted in Italy reported on the development of a similar system, the OncoCure CDSS [48].

Educational interventions

Seven studies described educational interventions targeting healthcare providers to promote compliance with breast cancer CPGs [44, 50, 55, 57,58,59, 63]. One intervention consisted in the provision of academic detailing on breast cancer screening (based on the American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of BC) among primary care physicians in an underserved community in the USA [50]. An intervention in seven hospitals in France consisted in monthly meetings where local opinion leaders presented the relevant sections of the CPGs, which were subsequently sent to all the participating physicians who were expected to use them in their practice [63]. Another intervention consisted in a comprehensive continuing medical education package to address pre-identified barriers to guideline adherence. The intervention followed a multimethod approach to physician education including CME conferences, physician newsletters, CBE skills training, BC CME monograph, “question of the month” among hospital staff meetings, primary care office visits, and patient education materials [57, 58]. An educational intervention to improve compliance with radiological staging CPGs in early breast cancer patients [59] consisted of multidisciplinary educational rounds, presenting the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines [72]. Another intervention, aimed to support compliance with recommendation against serum tumor marker tests and advanced imaging for BC survivors who are asymptomatic for recurrence, consisted in academic detailing for oncologists at regular meetings [55]. Another intervention [44] consisted in an online course to learn to implement and deliver the Strength after Breast Cancer (SABC) guidelines (with recommendations about rehabilitative exercise for breast cancer survivors).

Audit and feedback interventions

We identified two audit and feedback interventions [47, 69]. One consisted in sending hospitals a written report with regional benchmark information on nine performance indicators measuring the quality of care based on breast cancer national guidelines [69]. Healthcare professionals attended sessions twice a year, where an anonymous benchmark was presented for each hospital score compared with the regional mean and the norm scores. Another intervention [47] audited patients’ medical records according to four agreed indicators. Information from the audit forms was entered into a database, which allowed individualized reports for each participating clinician, providing detailed feedback about their practice, with comparisons across the group and against the agreed criteria.

Other types of single component interventions

Five studies described other strategies to promote compliance with breast cancer CPGs [45, 49, 52, 56, 61, 70]. One intervention consisted on a microcomputer tickler system on the ordering of mammograms [45]. The system displayed the date of the last mammogram ordered in the “comments” section of the encounter form for each visit. An intervention to support compliance with CPGs follow up recommendations in low-income breast cancer survivors [70] consisted in the implementation of a medical home program to support primary care case management. Providers and networks participating in this program received a payment per eligible patient per month for care coordination. Another intervention consisted in the implementation of new clinical pathways supplemented by clinical vignettes [56]. Another intervention consisted in an integrated knowledge translation strategy to be used by guideline developers to improve the uptake of their new CPGs on breast cancer screening [61]. This integrated knowledge translation strategy was based on the Knowledge to Action Framework [73], and involved the identification of barriers to knowledge use. An intervention to support compliance with the Dutch breast cancer guideline [52] consisted of a medical critiquing system (computational method for critiquing clinical actions performed by physicians). The system aimed at providing useful feedback by finding differences between the actual actions and a set of ‘ideal’ actions as described by a CPG.

Multifaceted interventions

We identified nine multifaceted interventions [36, 37, 46, 49, 51, 53, 54, 60, 62]. One intervention to increase compliance with mammography screening [37] consisted of (i) audit results and a comparison with the network benchmark; (ii) academic detailing of exemplar principles and information from the medical literature; (iii) services of a practice facilitator for 9 months who helped the practitioners design their interventions and facilitate “Plan, Do, Study, Act” processes; and iv) information technology support. In another intervention [60] to increase screening mammography, primary care providers received (i) a fact sheet providing current information on screening mammography for older women; (ii) telephone follow-up of any questions, and; (iii) copies of a simply written pamphlet on mammography that they could distribute to patients. Another intervention [54] consisted of biannual feedback to primary care providers regarding compliance with cancer screening CPGs and financial bonuses for “good” performers. Feedback reports documented a site’s scores on each screening measure and a total score across all measures, as well as plan-wide scores for comparison. Another intervention [51] consisted of an educational intervention accompanied by cue enhancement using mammography chart stickers, and by feedback and token rewards. Another intervention [46] included (i) use of standardized patients to observe and record healthcare professionals’ performance followed by direct feedback; (ii) newsletters to inform healthcare providers about screening methods; (iii) posters and cards presenting key points about CBE and the importance of routine screening mammograms, and; (iv) patient education materials. An intervention to improve compliance with new CPGs by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) on the proper use of hypofractionation [49] consisted in implementing five consensus-driven and evidence-based clinical directives to guide adjuvant radiation therapy for breast cancer. Prospective contouring rounds were instituted, wherein the treating physicians presented their directive selection and patient contours for peer-review and consensus opinion. Another intervention combined audit and feedback and education to providers to increase compliance with breast cancer treatment guidelines [62]. Repeated feedback on the performance of the chemotherapy administration, timing and dosing were given to the participants. The feedback consisted of a demonstration of variation in performance between the different hospitals and the region as a whole. The educational component consisted in four consecutive sessions of discussion about relevant literature that became available in that period regarding chemotherapy dose intensity, sequencing of radiotherapy and the importance of adequate axillary lymph node clearance.

An intervention to promote compliance with new National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from routine testing to omission of ordering complete blood cell count and liver function tests in patients with early breast cancer [53] involved (i) provision of educational materials; (ii) audit and feedback; (iii) certification; (iv) patient education; (v) financial incentives and (vi) implementation of alerts in the electronic medical records. Another intervention to promote breast cancer screening CPGs [36] included (i) printed educational materials with the recommendations for breast cancer mammography, (ii) printed educational materials with CPGs recommendations for clinical breast exams and breast self-exams, and (iii) video (12 min) directed at clinicians, exploring strategies for patient discussion around breast cancer screening issues.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was judged as low in five studies [45, 53, 54, 59, 70], moderate in ten [36, 37, 42, 44, 47, 56,57,58, 62, 63], and high in five [46, 49, 50, 55, 65]. In four studies [51, 52, 60, 69] the risk of bias was unclear since there was not enough information available to determine potential biases. We did not assess risk of bias for case studies, due to the lack of appropriate tools available. A detailed description of the risk of bias of the included studies, excluding case studies, is available in Additional file 3.

Impact of the interventions

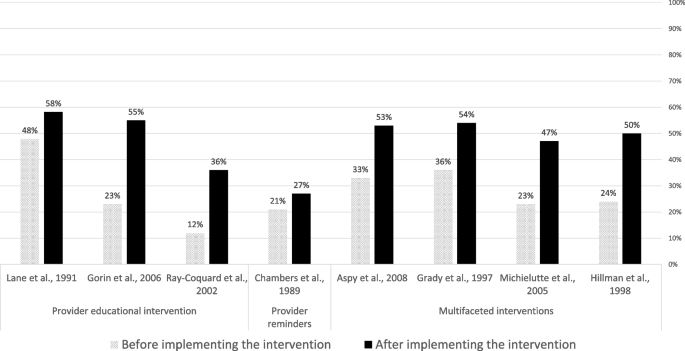

Six RCTs [37, 45, 50, 51, 54, 60] and four controlled before-after studies [50, 57, 58, 63] examined the effectiveness of four provider educational interventions, one intervention based on the use of provider reminders, and five multifaceted interventions. In nine of these interventions (90%), the ultimate goal was to improve compliance with breast cancer screening guidelines. Compliance was uniformly measured in terms of mammography rates (e.g., proportion of eligible women undergoing a mammography screening for breast cancer). Except one multifaceted intervention [54], the interventions consistently showed relevant beneficial effects (Fig. 2).

Impact of educational interventions

Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of educational interventions targeted to healthcare providers [50, 57, 58, 63]. A randomized controlled trial showed that the intervention improved recommendation of mammography (odds ratio (OR) 1.85, 95% CI 1.25–2.74) and clinical breast examination (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.31–3.46) in female patients aged 40 and over [50]. One controlled before-after study showed significant (p < 0.05) improvements in providers’ knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy towards the new CPG screening recommendations [57], whereas another controlled before-after study reported a significant improvement in the number of reported mammography referrals of asymptomatic women aged 50 to 75 years in the intervention group but not in the control group [58]. A controlled before-after study observed an improved compliance to diagnostic and treatment CPG recommendations in the intervention group (from 12% before the intervention to 36% post-intervention; P < 0.001), whereas no significant improvements were observed in the control group [63].

Impact of provider reminders

A randomized controlled trial [45] showed that a microcomputer-generated reminder system for ordering mammograms improved compliance with mammography guidelines: 27% (170/639) in the intervention vs 21% (128/623) in the control group (OR = 1.40 (95%CI = 1.01 to 1.82); p = 0.011) after 6 months follow-up.

Impact of multifaceted interventions

Five studies examined the impact of multifaceted interventions. A randomized controlled trial observed that, in comparison with usual care, a multifaceted intervention (including audit and feedback; provider education; information technology support) increased the proportion of women offered a mammogram (38% vs 53%), and the proportion of women with a recorded mammogram (35% vs 52%) [37]. Another trial observed that a multifaceted intervention (comprising provider education and patient education through pamphlets), did not improve compliance with screening mammography guidelines in the overall sample, but produced significant improvements in specific vulnerable subgroups (elderly, lower educational attainment, black ethnicity and with no private insurance) [60]. A randomized controlled trial observed that a multifaceted intervention (audit and feedback plus financial incentives) doubled screening rates both in the intervention and control groups, with no statistically significant differences observed between groups [54]. A trial examining a multifaceted intervention (provider education, cue enhancement plus feedback, and token rewards) observed that mammography compliance rates significantly improved (p < 0.05) in the intervention (62.8%) in comparison with the control (49.0%) group [51]. A controlled before-after study observed that a multifaceted intervention (including audit and feedback, patient and professional education) improved the demonstration of breast cancer screening, with significantly more women older than 50 receiving mammograms in the intervention than in the comparison group [46].

Certainty of evidence

The results from the assessment of the certainty of evidence concerning the impact of the interventions on compliance with breast cancer CPGs is available in Additional file 5. Based on GRADE criteria, we rated the certainty of evidence as “low” for the four educational interventions targeting healthcare providers. This was due to very serious risk of bias, for which we downgraded the level of evidence two levels. For the only intervention identified consisting in a reminder system for healthcare providers, we rated the certainty of evidence as “moderate” (downgrading one level due to serious indirectness). For the five multifaceted interventions, we rated the evidence as “low”, due to serious risk of bias, and serious inconsistency.

Discussion

Main findings

In this systematic review, we identified 35 studies describing and evaluating the impact of interventions to support clinician compliance with breast cancer CPGs. We described a range of different types of interventions to support adherence of healthcare professionals to breast cancer CPGs. We observed that there is low quality evidence that educational interventions targeted at healthcare professionals may improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. There is moderate quality of evidence that reminder systems for healthcare professionals improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening. There is low quality of evidence that multifaceted interventions may improve compliance with recommendations concerning breast cancer screening. The effectiveness of the remaining types of interventions identified is uncertain, given the study designs available (e.g., cross-sectional, uncontrolled before-after or case studies). There is very limited data on the costs of implementing these interventions.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this systematic review is that it addressed a highly relevant question, and provided much needed evidence to help improve providers’ compliance with breast cancer guidelines globally. An additional strength is that, contrary to previous systematic reviews, ours was not limited to experimental studies. By including observational, and qualitative and mixed-methods studies, we were able to provide a richer characterization of the available interventions.

This review has several limitations. First, we restricted the bibliographic searches to peer-reviewed publications in English language only. This may have resulted in failing to identify additional relevant data that could have further informed our assessments of the available evidence. However, we think that the impact of this limitation is likely to be small, as suggested by a recent meta-epidemiologic study [74]. Second, the heterogeneity of the reporting of outcome data made meta-analysis not feasible. Third, the heterogeneity in outcomes and the large number of strategies used across studies precluded us to determine the unique influence of each strategy on a given outcome.

Our results in the context of previous research

An important finding of our review is that most of the included studies showed that the interventions were effective in improving compliance to CPGs. This is in line with findings from previous, non-condition-specific reviews, which concluded that guideline dissemination and implementation strategies are likely to be efficient [75, 76].

A large proportion of the studies included in our review examined the impact of Computerized Decision Support Systems (CDSS). Previous systematic reviews observed that CDSS significantly improve clinical practice [77, 78]. In our review, the evidence about CDSS was only available from observational, uncontrolled studies, and was restricted to two tools in France and Italy in the hospital setting. New studies evaluating other CDSS, and in other settings and countries, are therefore needed.

There is substantial evidence from non-condition specific research that audit and feedback interventions can effectively improve quality of care [79]. A recent systematic review [80] examining the effectiveness of cancer (all types) guideline implementation strategies showed that providing feedback on CPG compliance was associated with positive significant changes in patient outcomes. More research is needed about the impact of audit and feedback interventions on the compliance with breast cancer CPGs.

Educational interventions targeted to providers (both in isolation and in combination with other interventions) have shown to improve outcomes in patients with cancer [80]. Despite the low certainty obtained, the studies in our review consistently showed that educational and multifaceted interventions improve compliance with breast cancer CPGs, supporting also results from previous non-condition specific reviews [16, 81], as well as current recommendations from the Institute of Medicine [82].

In line with our finding concerning electronic reminder interventions, a Cochrane systematic review concluded that computer‐generated reminders to healthcare professionals probably improves compliance with preventive guidelines [83].

Implications for practice and research

In terms of implications for practice, given that compliance with breast cancer guidelines is associated with better survival outcomes [25], and that there are still a substantial proportion of breast cancer patients not receiving clinical guidelines recommended care [21], it is important that the most effective interventions available are implemented to improve breast cancer guideline uptake by healthcare providers.

In terms of implications for research, as in a previous non-condition-specific review [76], we observed that there is very limited data on the costs of implementing the interventions to support compliance with breast cancer CPGs, as well as a scarcity of studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions targeting the organization of care (e.g., benchmarking tools). Research in these two areas is urgently needed to allow evidence-based decisions concerning which interventions should be rolled out and implemented widely as part of existing quality improvement programs. Also worth noting is that, up to now, the great majority of the research on this (breast cancer) area has focused on measuring the impact of the interventions on process measures (mostly compliance rates). No study measured the impact on patient outcomes, and only a small minority examined the impact on determinants of compliance behavior (e.g., providers’ knowledge, attitudes, or self-efficacy). Future research would benefit from including a broader range of outcomes (including proximal and distal), as this would help to better measure and understand the extent to which the interventions produce the intended benefits.

Future research is also needed to identify the most effective types of interventions in improving CPGs uptake, as well as the “active ingredients” of multifaceted interventions [84]. The characteristics of the CPGs intended users, and the context in which the clinical practice occurs are likely to be as important as guideline attributes for promoting adoption of CPG recommendations. Therefore, future research should focus on gaining a deeper understanding about how, when, for whom, and under which circumstances the interventions identified can effectively support guideline adherence. Using a realist evaluation methodology [85] may prove a valuable strategy in this endeavor. However, as observed in our review, the detailed characteristics of the interventions are very frequently scarcely reported. To allow progress in this area, it is of utmost importance that intervention developers and researchers offer in their published reports a comprehensive characterization of their interventions. The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines [86] were specifically designed for this purpose.

Conclusion

Promoting the uptake and use of CPGs at the point of care, represents a final translation step, from scientific findings into practice. In this review we identified a wide range of interventions to support adherence of healthcare professionals to breast cancer CPGs. Most of them are based on computerized decision support systems, provision of education, and audit and feedback, which are delivered either in isolation or in combination with other co-interventions. The certainty of evidence is low for educational interventions. The evidence is moderate for automatic reminder systems, and low for multifaceted interventions. For the rest of the interventions identified, the evidence is uncertain. Future research is very much needed to strengthen the available evidence base, concerning not only their impact on compliance, but also on patient important outcomes, and on their cost-effectiveness.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ASTRO:

-

American Society for Radiation Oncology

- CDSS:

-

Computerized Decision Support Systems

- CPG:

-

Clinical Practice Guidelines

- EPOC:

-

Effective Practice and Organization Care

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RoB:

-

Risk of bias

- SABC:

-

Strength after Breast Cancer

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Bozzi LM, Stuart B, Onukwugha E, Tom SE. Utilization of screening mammograms in the medicare population before and after the affordable care act implementation. J Aging Health. 2020;32(1):25–32.

Sestak I, Cuzick J. Update on breast cancer risk prediction and prevention. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(1):92–7.

van Luijt PA, Fracheboud J, Heijnsdijk EA, den Heeten GJ, de Koning HJ. Nation-wide data on screening performance during the transition to digital mammography: observations in 6 million screens. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2013;49(16):3517–25.

Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, Fryback DG, Clarke L, Zelen M, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. NEngl J Med. 2005;353(17):1784–92.

Gangnon RE, Stout NK, Alagoz O, Hampton JM, Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A. Contribution of breast cancer to overall mortality for US women. Med Decis Mak. 2018;38(1_suppl):24s–31s.

Kalager M, Zelen M, Langmark F, Adami HO. Effect of screening mammography on breast-cancer mortality in Norway. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1203–10.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. Evidence-based implementation of evidence-based medicine. Jt Comm J Qual Improve. 1999;25(10):503–13.

Green LA, Seifert CM. Translation of research into practice: why we can’t “just do it.” J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(6):541–5.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-Based Research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH Roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–6.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ. 1998;317(7156):465–8.

Flodgren G, O’Brien MA, Parmelli E, Grimshaw JM. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6(6):Cd000125.

Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966-1998. J Gen Internal Med. 2006;21 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S14-20.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):Ii2-45.

Henry NL, Hayes DF, Ramsey SD, Hortobagyi GN, Barlow WE, Gralow JR. Promoting quality and evidence-based care in early-stage breast cancer follow-up. J Natl Cancer Institute. 2014;106(4):dju034.

Keikes L, van Oijen MGH, Lemmens V, Koopman M, Punt CJA. Evaluation of guideline adherence in colorectal cancer treatment in The Netherlands: a survey among medical oncologists by the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17(1):58–64.

Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med. 2004;38(5):536–50.

Carpentier MY, Vernon SW, Bartholomew LK, Murphy CC, Bluethmann SM. Receipt of recommended surveillance among colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7(3):464–83.

Niño de Guzmán E, Song Y, Alonso-Coello P, Canelo-Aybar C, Neamtiu L, Parmelli E, et al. Healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer guidelines in Europe: a systematic literature review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(3):499–518.

Ament SM, de Groot JJ, Maessen JM, Dirksen CD, van der Weijden T, Kleijnen J. Sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12): e008073.

Ferron G, Martinez A, Gladieff L, Mery E, David I, Delannes M, et al. Adherence to guidelines in gynecologic cancer surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(9):1675–8.

Bahtsevani C, Uden G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):427–33.

Ricci-Cabello I, Vásquez-Mejía A, Canelo-Aybar C, Niño de Guzman E, Pérez-Bracchiglione J, Rabassa M, et al. Adherence to breast cancer guidelines is associated with better survival outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies in EU countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):920.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355: i4919.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH). Quality assessment tool for before-after (Pre-Post) study with no control group. 2021. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools . Last Accessed 4 Feb 2022 .

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12): e011458.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy; 2015. epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (Accessed 11 May 2022).

EPOC. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Resources for review authors, 2017. epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors (Accessed 9 Feb 2023). 2017.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):380–2.

Armson H, Roder S, Elmslie T, Khan S, Straus SE. How do clinicians use implementation tools to apply breast cancer screening guidelines to practice? Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):79.

Aspy CB, Enright M, Halstead L, Mold JW. Improving mammography screening using best practices and practice enhancement assistants: an Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(4):326–33.

Bouaud J, Blaszka-Jaulerry B, Zelek L, Spano JP, Lefranc JP, Cojean-Zelek I, et al. Health information technology: use it well, or don’t! Findings from the use of a decision support system for breast cancer management. AMIA Annu SympProc AMIA Symp. 2014;2014:315–24.

Bouaud J, Pelayo S, Lamy JB, Prebet C, Ngo C, Teixeira L, et al. Implementation of an ontological reasoning to support the guideline-based management of primary breast cancer patients in the DESIREE project. Artificial Intell Med. 2020;108: 101922.

Bouaud J, Seroussi B. Impact of site-specific customizations on physician compliance with guidelines. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2002;90:543–7.

Bouaud J, Seroussi B. Revisiting the EBM decision model to formalize non-compliance with computerized CPGs: results in the management of breast cancer with OncoDoc2. AMIA Annu Symp Proc AMIA Symp. 2011;2011:125–34.

Bouaud J, Seroussi B, Antoine EC, Zelek L, Spielmann M. A before-after study using OncoDoc, a guideline-based decision support-system on breast cancer management: impact upon physician prescribing behaviour. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84(Pt 1):420–4.

Bouaud J, Spano JP, Lefranc JP, Cojean-Zelek I, Blaszka-Jaulerry B, Zelek L, et al. Physicians’ attitudes towards the advice of a guideline-based decision support system: a case study with OncoDoc2 in the management of breast cancer patients. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:264–9.

Calo WA, Doerksen SE, Spanos K, Pergolotti M, Schmitz KH. Implementing Strength after Breast Cancer (SABC) in outpatient rehabilitation clinics: mapping clinician survey data onto key implementation outcomes. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:69.

Chambers CV, Balaban DJ, Carlson BL, Ungemack JA, Grasberger DM. Microcomputer-generated reminders. Improving the compliance of primary care physicians with mammography screening guidelines. J Fam Pract. 1989;29(3):273–80.

Coleman EA, Lord J, Heard J, Coon S, Cantrell M, Mohrmann C, et al. The Delta project: increasing breast cancer screening among rural minority and older women by targeting rural healthcare providers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(4):669–77.

Craft PS, Zhang Y, Brogan J, Tait N, Buckingham JM. Implementing clinical practice guidelines: a community-based audit of breast cancer treatment. Med J Aust. 2000;172(5):213–6.

Eccher C, Seyfang A, Ferro A. Implementation and evaluation of an Asbru-based decision support system for adjuvant treatment in breast cancer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014;117(2):308–21.

Gilbo P, Potters L, Lee L. Implementation and utilization of hypofractionation for breast cancer. Adv Radiation Oncol. 2018;3(3):265–70.

Gorin SS, Ashford AR, Lantigua R, Hossain A, Desai M, Troxel A, et al. Effectiveness of academic detailing on breast cancer screening among primary care physicians in an underserved community. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(2):110–21.

Grady KE, Lemkau JP, Lee NR, Caddell C. Enhancing mammography referral in primary care. Prev Med. 1997;26(6):791–800.

Groot P, Hommersom A, Lucas PJ, Merk RJ, ten Teije A, van Harmelen F, et al. Using model checking for critiquing based on clinical guidelines. Artificial Intell Med. 2009;46(1):19–36.

Hill LA, Vang CA, Kennedy CR, Linebarger JH, Dietrich LL, Parsons BM, et al. A strategy for changing adherence to national guidelines for decreasing laboratory testing for early breast cancer patients. Wisconsin Med J. 2018;117(2):68–72.

Hillman AL, Ripley K, Goldfarb N, Nuamah I, Weiner J, Lusk E. Physician financial incentives and feedback: failure to increase cancer screening in Medicaid managed care. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1699–701.

Kreizenbeck KL, Wong T, Jagels B, Smith JC, Irwin BB, Jensen B, et al. A pilot study to increase adherence to ASCO Choosing Wisely recommendations for breast cancer surveillance at community clinics. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29_suppl):18.

Kubal T, Peabody JW, Friedman E, Levine R, Pursell S, Letson DG. Using vignettes to measure and encourage adherence to clinical pathways in a quality-based oncology network: an early report on the moffitt oncology network initiative. Managed Care (Langhorne, Pa). 2015;24(10):56–64.

Lane DS, Messina CR, Grimson R. An educational approach to improving physician breast cancer screening practices and counseling skills. Patient Educ Counsel. 2001;43(3):287–99.

Lane DS, Polednak AP, Burg MA. Effect of continuing medical education and cost reduction on physician compliance with mammography screening guidelines. J Family Pract. 1991;33(4):359–68.

McWhirter E, Yogendran G, Wright F, Pharm GD, Clemons M. Baseline radiological staging in primary breast cancer: impact of educational interventions on adherence to published guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):647–50.

Michielutte R, Sharp PC, Foley KL, Cunningham LE, Spangler JG, Paskett ED, et al. Intervention to increase screening mammography among women 65 and older. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(2):149–62.

Munce S, Kastner M, Cramm H, Lal S, Deschene SM, Auais M, et al. Applying the knowledge to action framework to plan a strategy for implementing breast cancer screening guidelines: an interprofessional perspective. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(3):481–7.

Ottevanger PB, De Mulder PH, Grol RP, van Lier H, Beex LV. Adherence to the guidelines of the CCCE in the treatment of node-positive breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2004;40(2):198–204.

Ray-Coquard I, Philip T, de Laroche G, Froger X, Suchaud JP, Voloch A, et al. A controlled “before-after” study: impact of a clinical guidelines programme and regional cancer network organization on medical practice. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(3):313–21.

Seroussi B, Bouaud J, Antoine EC. ONCODOC: a successful experiment of computer-supported guideline development and implementation in the treatment of breast cancer. Artificial Intell Med. 2001;22(1):43–64.

Seroussi B, Bouaud J, Gligorov J, Uzan S. Supporting multidisciplinary staff meetings for guideline-based breast cancer management: a study with OncoDoc2. AMIA Annu Symp Proc AMIA Symp. 2007:656-60.

Seroussi B, Laouenan C, Gligorov J, Uzan S, Mentre F, Bouaud J. Which breast cancer decisions remain non-compliant with guidelines despite the use of computerised decision support? Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1147–56.

Seroussi B, Soulet A, Messai N, Laouenan C, Mentre F, Bouaud J. Patient clinical profiles associated with physician non-compliance despite the use of a guideline-based decision support system: a case study with OncoDoc2 using data mining techniques. AMIA Annu Symp Proc AMIA Symp. 2012;2012:828–37.

Seroussi B, Soulet A, Spano JP, Lefranc JP, Cojean-Zelek I, Blaszka-Jaulerry B, et al. Which patients may benefit from the use of a decision support system to improve compliance of physician decisions with clinical practice guidelines: a case study with breast cancer involving data mining. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;192:534–8.

Veerbeek L, van der Geest L, Wouters M, Guicherit O, Does-den Heijer A, Nortier J, et al. Enhancing the quality of care for patients with breast cancer: seven years of experience with a Dutch auditing system. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(8):714–8.

Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, Goyal RK, Lich KH, Lin CC, Moore A, et al. Is medical home enrollment associated with receipt of guideline-concordant follow-up care among low-income breast cancer survivors? Med Care. 2013;51(6):494–502.

CancerEst. Principes de prise en charge des cancers du sein en situation non me´tastatique: le re´fe´rentiel CancerEst. 2008.

Nofech-Mozes S, Vella ET, Dhesy-Thind S, Hanna WM. Cancer care Ontario guideline recommendations for hormone receptor testing in breast cancer. Clin Oncol (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)). 2012;24(10):684–96.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Continuing Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Dobrescu AI, Persad E, Stevens A, Garritty C, et al. Excluding non-English publications from evidence-syntheses did not change conclusions: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118:42–54.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2004;8(6):iii–iv, 1–72.

Flodgren G, Hall AM, Goulding L, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Leng GC, et al. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:Cd010669.

Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765.

Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–38.

Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, O’Brien MA, French SD, et al. Growing literature, stagnant science? Systematic review, meta-regression and cumulative analysis of audit and feedback interventions in health care. J Gen Internal Med. 2014;29(11):1534–41.

Tomasone JR, Kauffeldt KD, Chaudhary R, Brouwers MC. Effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies on health care professionals’ behaviour and patient outcomes in the cancer care context: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):41.

Giguère A, Zomahoun HTV, Carmichael PH, Uwizeye CB, Légaré F, Grimshaw JM, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):Cd004398.

Greenfield S, Steinberg E, Auerbach A, Avorn J, Galvin R, Gibbons R. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. p. 2017.

Arditi C, Rège-Walther M, Durieux P, Burnand B. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):Cd001175.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337: a1655.

Pawson R, Tilley N, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation: sage; 1997.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348: g1687.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The systematic review was carried out by the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center under Framework contract 443094 for procurement of services between European Commission Joint Research Centre and Asociación Colaboración Cochrane Iberoamericana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP, ZSP, and LN contributed to conception and design of the study. IS designed the literature search. IRC ENG, LN, ZSP, EP, DC, APVM, and GPM performed the literature screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal of included studies. PAC and IRC evaluated the certainty of evidence. All authors contributed to data interpretation. IRC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (literature review).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (the manuscript does not contain data from any individual person).

Competing interests

EP, LN, and ZSP are or were employees of the Joint Research Centre, European Commission. ENDG, DR, IS, and PAC are employees of the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategy.

Additional file 3.

Summary of Risk of Bias Assessment.

Additional file 4.

Characteristics and results of the 35 studies included in the review.

Additional file 5.

Evidence Profiles.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricci-Cabello, I., Carvallo-Castañeda, D., Vásquez-Mejía, A. et al. Characteristics and impact of interventions to support healthcare providers’ compliance with guideline recommendations for breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Implementation Sci 18, 17 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01267-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-023-01267-2